“Seventy percent of the world’s extreme poor are women”. If you’ve encountered this statistic before, please raise your hand. That is a lot of hands. And yet, this is what we call a

‘zombie statistic’: often quoted but rarely, if ever, presented with a source from which the number can be replicated. In fact, what we know from existing data is that women account for about 50 percent,

not 70 percent, of the world’s extreme poor—although, as we argue below, this does not mean poverty is gender neutral.

We have such questionable “facts” because existing poverty data makes it hard to have a clear picture of the true gender dimensions of poverty. Poverty is, generally, measured at the household level—meaning that if a household lives in extreme poverty, we assume that everyone under that roof lives at the same level of deprivation. However, evidence and common sense tell us that this is rarely the case; women, children, people with disabilities, and elders, for example, often receive smaller portions of food or have less invested in their education and health.

Ideally, we would have detailed, individual-level data to truly understand the depth and breadth of poverty among women in the world. However, given the difficulty that many countries face in gathering household-level data, which can be costly and time-consuming, this will be a challenge, but one we are beginning to tackle.

The good news is that, despite the limitations, we can still learn a lot about the differences in poverty between men and women in the meantime. This is the focus of a collaborative effort by UN Women and the World Bank, which uses the World Bank’s Global Monitoring Database (GMD) to analyze gender differences in welfare at the global level. The database covers 89 countries, representing approximately 84 percent of the population in the developing world – or about 5.2 billion individuals in 2013. Our paper uses data from all 89 countries for most estimates, and for some related to labor participation, a restricted sample of only 71 of these countries (roughly 75 percent of the developing world population). We use the International Poverty Line ($1.90 a day) for all the estimates. Here is what we found:

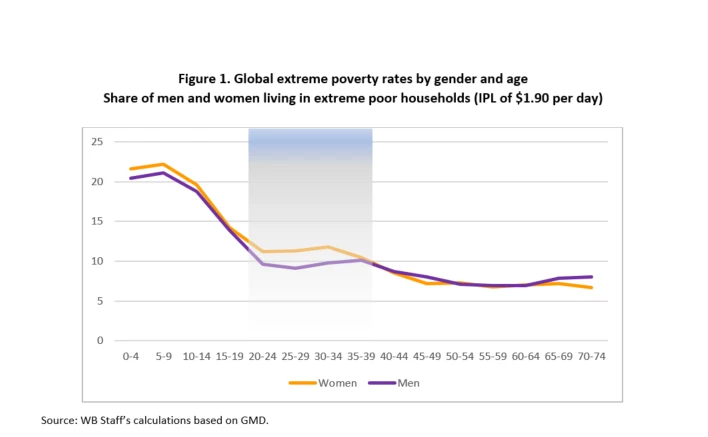

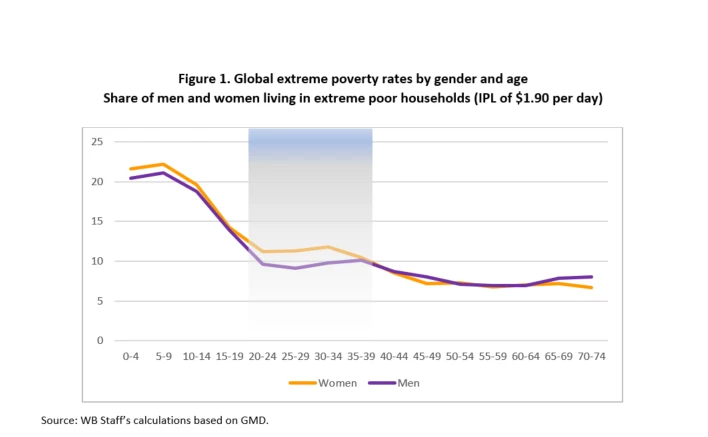

Children account for 44 percent of the global extreme poor and poverty rates are highest among children , particularly among girls (Figure 1). There are 105 girls for every 100 boys living in extreme poor households, across all ages.

As boys and girls get older, the gender gap in poverty widens further. 122 women between the ages of 25 and 34 live in poor households for every 100 men of the same age group. This coincides with the peak productive and reproductive ages of men and women, and likely reflects that as young women become wives and mothers, they often stop working in order to care for their husbands and children. This is not uniform across regions, however: Europe and Central Asia, the region with the lowest extreme poverty rate, also has the smallest gender poverty gap, while Sub-Saharan Africa, home to most of the global extreme poor, has the largest gender poverty gap.

Gender differences in poverty rates even out between the ages of 40 and 65, but emerge again in the elderly years in reverse. The share of men over the age of 65 living in poor households is higher than that of women---7.3 compared to 6.7 percent respectively.

Marriage, divorce, separation and widowhood also affect poverty of men and women differently. Girls and boys who are married before the age of 18 see higher poverty rates than those who are married later. Similarly, marriage and childbearing are correlated with higher poverty rates for both men and women of peak childbearing and reproductive age (18-49 years old). Although widows represent a small share of the poor population below age 65, widowhood is associated with higher poverty rates for men and especially women up to age 49. In adulthood, it seems that divorce and separation affect women more negatively than men, but do not necessarily translate into higher poverty rates compared to those of their married counterparts.

While most of the observed differences in poverty between men and women can be chalked up to differences in age and life events, there are still a few that cannot be explained by having children, lacking education, working for pay, or other household characteristics. These unexplained gender differences, which we call the poverty penalty, disproportionately affect young women and girls up to age 30. This poverty penalty accounts for about 5 million more women living in extreme poverty across the world, particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. This tells us that we need to look beyond the traditional reasons that can explain the differences in poverty between women and men, and explore more areas for meaningful action to help women, men, and entire families move out of poverty.

Our paper injects what we hope is some new, useful information to help explain gender differences in poverty across the lifecycle. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg; there is much more work needed. That’s why we have started to expand work on measuring what happens within households, first by looking beyond headship (see second part of the paper), and gathering more detailed information on consumption at the individual level (forthcoming in the next Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report). We are also building on experiments using alternative measures such as clothing in Malawi, asset ownership in Latin America, or nutritional status in Sub-Sahara Africa that help us find ways to overcome potential biases associated with assumptions about how resources are shared within households.

We hope to eventually replace the zombie statistic from above with a living, breathing, accurate understanding of the true depth of poverty among women in the world. This is not an attempt to make poverty more gender-equal, but rather to ensure that countries’ and communities’ efforts to end poverty do not leave anyone behind.

Note: The paper was co-authored by Ana Maria Munoz Boudet, Paola Buitrago, Benedicte Leroy de la Briere, David Newhouse, Eliana Rubiano, Kinnon Scott, and Pablo Suarez-Becerra.

We have such questionable “facts” because existing poverty data makes it hard to have a clear picture of the true gender dimensions of poverty. Poverty is, generally, measured at the household level—meaning that if a household lives in extreme poverty, we assume that everyone under that roof lives at the same level of deprivation. However, evidence and common sense tell us that this is rarely the case; women, children, people with disabilities, and elders, for example, often receive smaller portions of food or have less invested in their education and health.

Ideally, we would have detailed, individual-level data to truly understand the depth and breadth of poverty among women in the world. However, given the difficulty that many countries face in gathering household-level data, which can be costly and time-consuming, this will be a challenge, but one we are beginning to tackle.

The good news is that, despite the limitations, we can still learn a lot about the differences in poverty between men and women in the meantime. This is the focus of a collaborative effort by UN Women and the World Bank, which uses the World Bank’s Global Monitoring Database (GMD) to analyze gender differences in welfare at the global level. The database covers 89 countries, representing approximately 84 percent of the population in the developing world – or about 5.2 billion individuals in 2013. Our paper uses data from all 89 countries for most estimates, and for some related to labor participation, a restricted sample of only 71 of these countries (roughly 75 percent of the developing world population). We use the International Poverty Line ($1.90 a day) for all the estimates. Here is what we found:

Children account for 44 percent of the global extreme poor and poverty rates are highest among children , particularly among girls (Figure 1). There are 105 girls for every 100 boys living in extreme poor households, across all ages.

As boys and girls get older, the gender gap in poverty widens further. 122 women between the ages of 25 and 34 live in poor households for every 100 men of the same age group. This coincides with the peak productive and reproductive ages of men and women, and likely reflects that as young women become wives and mothers, they often stop working in order to care for their husbands and children. This is not uniform across regions, however: Europe and Central Asia, the region with the lowest extreme poverty rate, also has the smallest gender poverty gap, while Sub-Saharan Africa, home to most of the global extreme poor, has the largest gender poverty gap.

Gender differences in poverty rates even out between the ages of 40 and 65, but emerge again in the elderly years in reverse. The share of men over the age of 65 living in poor households is higher than that of women---7.3 compared to 6.7 percent respectively.

Marriage, divorce, separation and widowhood also affect poverty of men and women differently. Girls and boys who are married before the age of 18 see higher poverty rates than those who are married later. Similarly, marriage and childbearing are correlated with higher poverty rates for both men and women of peak childbearing and reproductive age (18-49 years old). Although widows represent a small share of the poor population below age 65, widowhood is associated with higher poverty rates for men and especially women up to age 49. In adulthood, it seems that divorce and separation affect women more negatively than men, but do not necessarily translate into higher poverty rates compared to those of their married counterparts.

While most of the observed differences in poverty between men and women can be chalked up to differences in age and life events, there are still a few that cannot be explained by having children, lacking education, working for pay, or other household characteristics. These unexplained gender differences, which we call the poverty penalty, disproportionately affect young women and girls up to age 30. This poverty penalty accounts for about 5 million more women living in extreme poverty across the world, particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. This tells us that we need to look beyond the traditional reasons that can explain the differences in poverty between women and men, and explore more areas for meaningful action to help women, men, and entire families move out of poverty.

Our paper injects what we hope is some new, useful information to help explain gender differences in poverty across the lifecycle. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg; there is much more work needed. That’s why we have started to expand work on measuring what happens within households, first by looking beyond headship (see second part of the paper), and gathering more detailed information on consumption at the individual level (forthcoming in the next Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report). We are also building on experiments using alternative measures such as clothing in Malawi, asset ownership in Latin America, or nutritional status in Sub-Sahara Africa that help us find ways to overcome potential biases associated with assumptions about how resources are shared within households.

We hope to eventually replace the zombie statistic from above with a living, breathing, accurate understanding of the true depth of poverty among women in the world. This is not an attempt to make poverty more gender-equal, but rather to ensure that countries’ and communities’ efforts to end poverty do not leave anyone behind.

Note: The paper was co-authored by Ana Maria Munoz Boudet, Paola Buitrago, Benedicte Leroy de la Briere, David Newhouse, Eliana Rubiano, Kinnon Scott, and Pablo Suarez-Becerra.

Join the Conversation