Florence Adino prepares fish at her restaurant on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kisumu, Kenya. She recently installed a rocket stove in her kitchen, which is more economical and cleaner than her old stove, allowing Adino to expand her business. Photo: Peter Kapuscinski / World Bank

Florence Adino prepares fish at her restaurant on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kisumu, Kenya. She recently installed a rocket stove in her kitchen, which is more economical and cleaner than her old stove, allowing Adino to expand her business. Photo: Peter Kapuscinski / World Bank

“What is the main fuel used for cooking?” asks a living standards survey. The responses are used to track progress toward the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 7: universal access to clean, sustainable, and affordable energy . According to the World Health Organization the slowest progress globally is in Africa, where only 20 percent of people rely primarily on clean fuels and technologies for cooking, compared to the global average of 69 percent.

The type of energy households use is important because using traditional solid fuels not only pollutes—harming health and causing 3.2 million premature deaths a year—but diverts time away from productive activities such as schooling due to the time spent collecting fuel. Wood fuel use can also lead to forest degradation and loss, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

From the energy ladder to energy stacking

But is shifting primary household energy to clean fuels and technologies enough to protect people’s health and free up adults and children from these daily chores? During the 1990s, the thinking was that households with more income moved up the “energy ladder”: a three-stone fire was on the lowest rung, more efficient wood stoves on the next rung, then charcoal and kerosene, and finally gas and electricity at the top. The cooking and heating patterns in high-income countries seemed to support this hypothesis: virtually all households in high-income regions cook and heat exclusively with gas or electricity.

But a study on rural Mexican households called the “energy ladder” theory into question, suggesting that stacking of multiple fuels and technologies for cooking more accurately described household energy use: even as disposable income increased, households did not abandon lower-rung fuels and technologies, but instead retained several fuel-technology combinations. In particular, many rural Mexican households continued to cook with wood even after adopting liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and some even increased wood consumption. Fuel stacking is problematic from a health perspective. Without abandoning polluting fuel use, noticeable improvements in health outcomes may not be realized.

But how rich do households in developing countries have to be to abandon polluting energy? A recent World Bank study analyzes national household surveys in 24 Sub-Saharan African countries. None had access to natural gas, leaving LPG and electricity as the two main sources of clean cooking energy. As in the rest of the developing world, households in a given country tended to choose mainly electricity or gas for clean cooking. For many households, power shortages and rolling blackouts make it difficult to rely primarily on electricity. Of the 24 countries sampled, there were 12 countries in which more than one-fifth of the population, either nationally (nine countries) or in urban areas (three countries), cited LPG as the primary cooking fuel.

Not surprisingly, those who were using LPG as their primary fuel were in the top 40 percent of per-capita-expenditure distribution. As well, households in the top 20 percent were most likely to abandon polluting fuels, with these households markedly richer on a per capita basis than others in the same quintile who had cited LPG as their primary cooking fuel but were also using polluting fuels.

Are smaller households “cleaner”?

One distinct characteristic of the households that use only clean cooking energy was that they were smaller than fuel-stacking households in the same quintile. In the top quintile, despite being richer, those using only LPG and electricity had fewer household members, making their total household expenditures lower than those of fuel-stacking households using LPG as their primary cooking fuel. Further, the expenditures on LPG of households who had abandoned polluting fuels were lower than those of fuel-stacking households—suggesting that they likely consumed less LPG—but the share of the total household expenditures spent on LPG was higher. Their higher LPG expenditure shares notwithstanding, the shares fell comfortably within the affordable range—less than 5 percent of the total household expenditures.

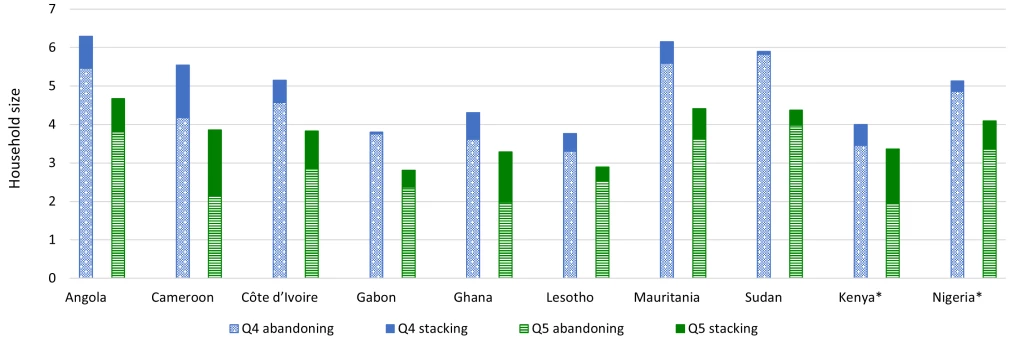

This suggests that smaller families find it easier to cook exclusively with gas and electricity. Such a conclusion would be consistent with the field observations that households use large wood stoves placed on the ground to prepare large dishes, especially if they require hours of cooking with vigorous stirring from time to time. However, when comparing households in the fourth and top expenditure quintiles, the average size of households using only clean energy in the fourth quintile was consistently larger than that of stacking households in the top quintile, as the figure below illustrates. These findings suggest that reasons other than affordability could be driving energy use patterns of households that otherwise would be able to abandon polluting fuels and technologies.

Comparison of sizes of households abandoning versus stacking polluting fuels

Source: World Bank staff calculations using household survey data.

Note: The solid portions are incremental household sizes for those staking fuels. For example, in the top quintile in Cameroon, the average size of households abandoning polluting fuels was 2.1, and that of the households stacking fuels was 3.9. * = urban households only; Q4 = quintile 4; Q5 = quintile 5; abandoning = households using LPG who had abandoned polluting fuels; stacking = households citing LPG as their primary cooking fuel and were using polluting fuels in parallel.

Non-financial barriers to clean household energy

By far the most important barrier to an abandonment of polluting fuels is financial, but the above findings point to non-financial barriers additionally determining the patterns of household energy use. Aside from cultural preferences, market factors may be playing an important role: not enough competition in the market, reducing the service quality; rampant commercial malpractice, such as underfilling new cylinders; obtaining a refill by going to the retail outlet being time-consuming and inconvenient, home delivery charges being too high, or both; and supply being unreliable. These reasons may even drive wealthier households not to rely exclusively on LPG. Regulatory reforms and enforcement of internationally acceptable standards and regulations to address these issues will not only help more households to shift entirely to clean fuels and technologies, but also help reduce costs by expanding the market size and taking advantage of economies of scale. Doing so will shift many more households to LPG over time as their primary cooking fuel and eventually as the only energy source alongside electricity.

Join the Conversation