Farmers in Dong Thap Province, southern Vietnam catch wild fish and raise shrimp during the flooding season.

Farmers in Dong Thap Province, southern Vietnam catch wild fish and raise shrimp during the flooding season.

In the floodplains of the upper Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam, the regular seasonal monsoon floods, lasting from late July until November, are replenishing the soil, rejuvenating the river ecosystems, and allowing farmers like Nguyen Van Khen to boost incomes through flood-based agriculture.

But floods could quickly turn into a problem if they get stronger than expected or go off cycle. Heavy flooding could wipe out farming areas overnight.

In the upper Mekong Delta, such irregularity comes in more often, prompting farmers to rethink their livelihood strategy. This is predicted to get worse with climate change.

During a recent trip to the Mekong Delta, we witnessed how a World Bank-financed project has significantly strengthened farmers’ ability to cope with the new reality. Embankments supported by the project help a large farming area withstand the floods while capturing the rich floodwater to nourish the crop.

First, it’s sinking, on average of about 1.1 centimeters per year, due to excessive groundwater extraction, sand mining, and reduced sediment deposition. This very threat to the Mekong Delta’s existence is compounded by sea level rise.

A conservative estimate from our Vietnam’s Country Climate and Development Report warns that almost half of the delta could be submerged if sea level rose by 75–100 centimeters, relative to 1980–1999 levels.

Second, it’s facing intense weather fluctuations.

Around the delta, the sea encroaches, carrying saltwater inland through its myriad of waterways. In better days, the Mekong River surged through the lower river basin, washing the salinity back out to sea. More recently the reduced river flow in the dry season has accelerated saline intrusion, a trend accentuated by droughts, as in 2020.

It’s not just wet and dry seasons. Extreme droughts and floods strike more often, with greater intensity. When Mother Nature goes off balance, the farmers bear most of the brunt. For example, saltwater can destroy an orchard worth several years of farmers’ investment and push them into bankruptcy.

Added to the challenge is the degradation of the environment due to many years of resource-intensive and unsustainable farming practices.

In 2017, the Government of Vietnam passed a much-needed resolution that embraces a new thinking – “actively living with nature.” With that, the development trajectory of the Mekong Delta has shifted. But what exactly does “actively living with nature” mean?

In the upper delta, local people used to divert the floodwater with dikes so that farmers could grow rice all year round. But this model is no longer economically profitable or ecologically sustainable.

As our project has proven, farmers can work with floodwater, instead of against it. During the flooding season, they can let water inundate their fields, turning them into the perfect setting for aquaculture. These aquatic resources have proven to bring in higher incomes than the third-crop rice. When the water recedes in the dry season, fish excreta and alluvium enrich the soil, making it fertile for growing the next crop.

Down in the Ca Mau peninsula, “actively living with nature” also means integrating mangrove forests as part of the solution. Previously, only sea dikes or wave breakers were used to prevent coastal erosion. Mangroves have proven to offer the flexibility that hard infrastructure often lacks when dealing with unpredictable coastal dynamics.

Such renewed appreciation for the benefits of mangrove forests helps slow down their clearance for shrimp farming. Instead, shrimp farmers find ways to raise shrimp under the mangrove cover, producing higher-value, eco-certified products that are in high demand in the international market.

Throughout the Mekong River delta, we’ve seen many examples of farmers who are adapting to a changing climate with the right practices. We could not be more thrilled to know that many of the sustainable livelihood models have been supported by our pioneering project.

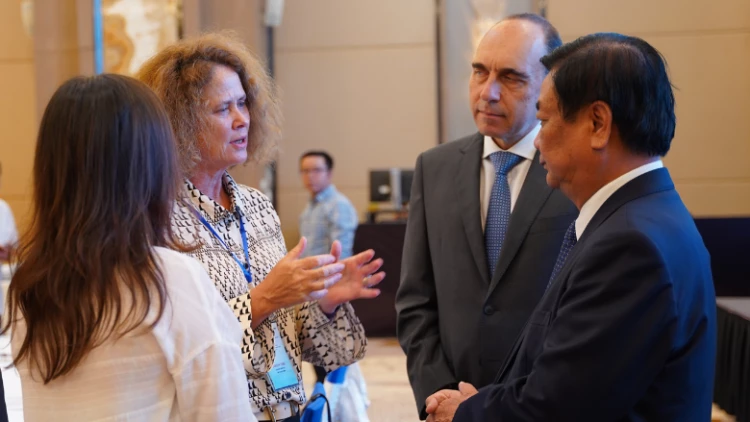

An official at the surface water monitoring station in Tra Vinh Province tells the visiting World Bank delegation how they have utilized the data to monitor the status of the Mekong River.

We are also excited about the future. It’s obvious that scaling up solutions that protect communities from environmental threats and help them thrive economically is not without challenges. Just as the problems they are designed to solve, policies and actions must be interprovincial and multidisciplinary.

In February this year, the Mekong Delta—with all its complex challenges—finally received a long-term integrated master plan. The master plan emphasizes the importance of a regional approach and the need to collaborate – rather than compete – among provinces and sectors over scarce resources. This point was echoed during our recent dialogue with the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development and provincial leaders in Can Tho City – the Mekong Delta’s heart.

We hope that upcoming actions and investments will match the regional master plan in scope and scale. Getting a clearer sense of how the region will move forward will help other stakeholders who also care about the future of the Mekong Delta like us come up with impactful programs.

In the recent dialogue with the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development and provincial leaders in Can Tho City, The World Bank applauds the Government of Vietnam for passing a long-term integrated master plan for the Mekong Delta and emphasizes the need for actions and investments that match its scope and scale.

Despite all the hardships many farmers might endure, everyone we talked with was brimmed with hope. They are perfect examples of resilience in the face of adversity. We are hopeful, too, that their future and the Mekong Delta’s future will be bright. And we are trying our best, in partnership with the Government of Vietnam, to turn promises into actions for the nearly 20 million people living in the delta.

Join the Conversation